London is calling – European Porcelain from the Marton Museum Collection

Ich freu mich für den Sammler Veljko Marton einen ausführlichen Beitrag über die Wiener Kaufrufe für seine erste Ausstellung in London verfasst zu haben, hier der Text in englischer Sprache zum Nachlesen:

Eighteenth century “Kaufruf” of the Viennese Porcelain Factory in the Marton Collection

Even today, the figures of a street vendor, with their cries and gestures, are still a familiar sight to many of us; Let us take for example the newspaper seller, flower peddler, or the familiar figure selling roasted chestnuts at Christmas time. Along this same line of thought, even the ice cream sellers one finds on the beach in southern Europe come to mind. Yet this practice in this day and age can perhaps be considered to be in decline, most notably with the diminishing numbers of country folk selling their homegrown produce locally.

In the eighteenth century the cries of the vendors were a part of everyday life. In Paris, London, Hamburg and Vienna, of the 18th century, one could hear the cries of these vendors ring through the streets. Naturally, the different vendors developed specific calls for the goods they were offering. This distinguished them from one another – this is where the German “Kaufruf”[1] came from, meaning a “selling-cry”. Contemporary paintings by Bernardo Bellotto[2] and engravings by Salomon Kleiner[3] and Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach[4]document the bustling street trade that went on in front of the residences of the aristocracy.

Through the refinement of eating practices and dining locales, along with the existing differentiations in eating practices in the mid-eighteenth century, there came to be two dominant trends in developing table culture. On the one hand was the coalescence of single form continuous displays, whose esthetics demanded, for the most part, the dessert table. On the other hand was the influence of the princely court, and the masquerade balls that had become very popular at the time. Having long ago lost the seriousness of baroque celebrations, these parties were grand affairs with everyone dressed according to a chosen theme. Subsequently, these court conditions required correspondingly fanciful and exotic table settings and cutlery. Aristocratic circles and the Courts barely realized or recognized the existing of the “Lower orders” and it became a fad to “discover” how such people lived. From this socio-historic context comes to us the multifaceted porcelain figures of the Vienna Porcelain Factory, executed between the years 1745 and 1785, that are testament to many of these interesting court practices.

In 1918 Edmund Wilhelm Braun[5] knew at least 65 different kinds of market crier figures made by the Vienna Porcelain Factory[6], Amongst the most popular were the “Haussierer” (door to door salesmen), “Verkäufer”(vendors), and “Professionisten”[7] (tradesmen)”. According to Vienna law, street vendors could only sell their wares on certain specific squares. Until today the street names inVienna such as Fleischmarkt (meat market), Kohlmarkt (coal market), Getreidemarkt (grain market) bear witness of their original function. Stores as we know them barely existed in the eighteenth century so many workmen carried their tools of trade with them at all times. Many vendors who lived in Vienna in the eighteenth century had no fixed address and some entrepreneurs hired actors from travelling troupes to hawk their wares in the streets. The definition of a “Kaufruf” (street crier) becomes more difficult. Is this a seller of his own produce or perhaps a retailer of another’s goods?

Martin Eberle attempts classification of the different types of Kaufruf according to Gotthard Brandler[8]:

- Crier in public service (ex. street lantern lighter)

- Salesperson (local or wandering)

- Trader of self made or grown products

- Wandering manual worker and casual labourers (ex. porter)

- Barterer (ex. flea market vendor, trash collector)

- Actors, juggler and street musicians (ex. bagpipe player, juggler)

- Urban types (ex. cleaner, beggar)

Creating the Models

The phenomenon of these itinerant people is certainly not specific to Vienna, it can also be seen in France, the “Cris de Paris” (cries of Paris) or in Germany, Italy and England. There are even known “Kaufruf” series originating from China, Russia and even the U.S.. One of the most well known series of “Cris de Paris” is made up of many pieces developed between 1737 and 1746 under the title “Etudes prises dans le bas peuple ou Les Cris de Paris” (Studies taken of the lower orders, otherwise known as the Cries of Paris). These artistically excellent studies by Edme Bouchardon depicted every sort of artisan and vendor, including sellers of food, porters next to entertainers and mountebanks. When Boucher published 1732 his series of engravings “Types de la rue et des Cris de Paris” (street types and cries of Paris) it became the archetype that Ravenet used as prototype for his own “Cris de Paris” engravings, which showed the street vendors as lively, light hearted folks. The Street Vendors enjoyed great popularity in Germany as well, especially since the manufactory at Meissen pioneered their creation as porcelain figures. Johann Joachim Kändler created in 1745 a first series modeled on the work of Graf Anne Claude Caylus. Ten years later another master craftsman, Peter Reinicke, with Kändler’s aid, rose to the challenge of this subject and with time created at least 36 different models based once more in part on Bouchardon and also drawings of the Parisian painter Christophe Huet.[9]

The Vienna Manufactory discovered in these French models a proper rendition for their early pieces of these miniature “sculptures” in the newly discovered material of porcelain. Since the Academy for Copper Engraving was first founded in Vienna by Jakob Mathias Schmutzer in 1766 there had been little or no figural models in the engravings for the early Viennese figures. Using Bouchardon’s series as a model, Johann Christian Brand (1722-1795), member of the Academy, began his “Großen Kaufruf” (Grand Series of Street Vendors) in 1773, resulting in the publication two years later of his “Zeichnungen nach dem gemeinen Volke besonders der Kaufruf in Wien” (Studies of the common people and especially the street vendors in Vienna).[10] The “Wiennerisches Diarium”[11] from 1775 contains appreciative words regarding the printing and the realism represented, along with the interest in local and foreign subject matter.[12] Brand´s 40 pages were very expensive and aimed at a new but erudite public with a high degree of taste, bored with the previous productions of the academy, specifically works with either historical or mythological content.[13] Most early Kaufrufe (Street vendors) depicted sharp-featured figures and actions set in the foreground, whereas later, during the Rococo period, it was the fashion to show the figures as elegant in their movements, softer in expression and even gay.

Picture 1: „Bretzenbäck“, Copper engraving after J.C. Brand, Vienna 1775

Picture 2: „Brezelverkäufer“, Vienna porcelain factory, about 1755-60, H 20,1 cm, Wien Museum Inv.Nr. K 69, 49.141

Viennese Kaufruf in the Marton Museum Collection

The earliest Kaufruf figure in the Marton Collection is doubtless the aproned Blacksmith. Leaning against a tree trunk as he is, with an anvil clearly visible, this pose is characteristic of early figural production. A documented figure carrying this pose from the Karl Mayer Collection, although unmarked, has been dated by Falke/Folnesics around 1760.[14] This blacksmith in question carries a Vienna mark which dates it between the years of 1744–1749. The undecorated base and clear movement of the figure are also indicative that it was made in an early period. Only a few of these early folk characters were created in the initial porcelain series: the trader with mousetraps and bellows[15], a vendor of vegetables graters[16], a miller, a Tyrolean bottle trader after a Meissen example, and a chimney sweep[17].

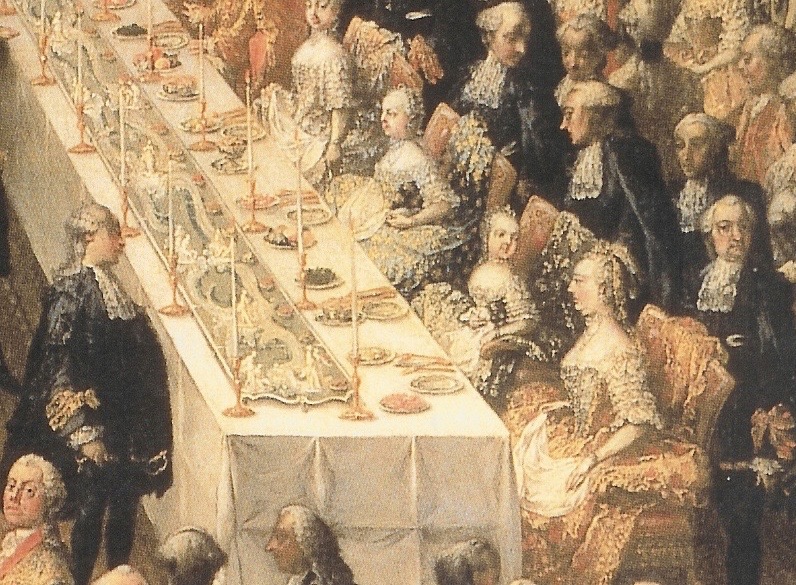

The “Bretzenbäck” or Pretzel baker conforms closely to the copper engraving “Boulanger des craquelins” in the first series of engravings by Brand in 1775.(see pic 1) The figure has elegantly disposed his limbs in a posture leaning on a rocky base and the Pretzels on the stick appear to be very fragile. His apron and its very fine buttons really represent the charm of the unpainted material, which enjoyed particular popularity at mid-century.[18]. Schemper-Sparholz postulated a relationship between the polished white surfaces of the rococo garden sculpture of the time, and the porcelain miniature “sculptures”[19] The oil painting by Meytens, showing the wedding of Joseph II. and Isabella von Parma in Vienna 1760 tells about the white based table decoration reminding the former used material as sugar or tragant.

Picture 3: Detail, Martin von Meytens, Wedding of Joseph II. and Isabella von Parma in the Redoutensaal, Vienna 1760, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

The Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague keeps a figure of a cavalier transformed into a pretzel seller by a different way of painting.[20]. The row of buttons on the shirt of the pretzel seller figure held in the Vienna Museum gave way to a gilded edge. (see pic 2) Even the headdress has a particularly folksy character. Both market criers use small trumpets to attract attention. Since this figure belongs to the first produced in mid-century, the question arises as to the model since the series by Brand was conceived two decades later. Again in the past it was often assumed that the Vienna figurines were modeled after nature and the copper engraver had not reached this pitch of endeavour. However a thouroughly organized manufactory could hardly manage in this way and there must have been another, today not known source used by the modelers.

The “Obst- und Gemüseverkäufer” (vendor of fruit and greenery) of the Marton Collection is from the earlier series of Kaufruf figures from the Vienna Factory.[21] The unglazed surface and plaster-like base, the rock rising to the hip and the compact body is without the delicacy of rococo figurines. It is interesting to see how varied the choice of fruits and vegetables was. Asparagus was a common vegetable at the beginning of the 17th century, and was probably prized more for its healing qualities than its good taste. Also this simple peasant, in the city to sell his wares, was executed without footwear. This feature also deserves some study, as it is most probably an example of aristocratic fantasy, rather than an accurate representation of peasant life. A high official at court, Johann Joseph Prince Khevenhüller-Metsch, reports from a so called “Redoute” in Schönbrunn Palace on the 30th of September, 1767, where the Empress emphatically advised him to masquerade. He goes on to write how his wife Karoline Gräfin Khevenhüller-Metsch “…dressed herself up as a peasant woman and dispensed various treats including pastries and candy…”[22]. It is also possible that on these occasions, the court conditor had to model such vegetables sweats shaped out of sugar or marchpane.[23]

The colourful “Fischverkäuferin” (female fish vendor) carries a platter of fish under her left arm. As the classic representative of the street seller, she is garbed similar to a cook: with an apron for holding as well as a shirt opened at the bosom that may be attributable to an erotic caprice on the artist’s part. The overflowing, gold bordered bodice, as well as the courtly hairstyle visible under the woman’s headdress, are indications that the piece was modelled as a court lady mascherading as a peasant woman. The fine floral design of the skirt, taken from the dress of the time, is a hint that the piece was made towards the end of the Rococo period. The brisk activity of a Vienna market place during the Baroque period, documented by Fischer/Delsenbach “Prospect des Hohen Marckts zu Wien. … Der Ort wo die Hausen, und andere Fische verkaufft werden” (Vienna High Market… the place where fish and other items were sold) here we see the full range of figures along with the city numbers of troughs, in which the goods on sale went not to waste.[24]

Another itinerant seller familiar to all sections of the aristocracy was the Schnapsverkäufer (vendor of liquor or Schnaps)[25]. This vendor sells the wares of his homeland, crying out in bad German, much like the “Zwiefel-Krowat” (Croatian onion vendor)[26], the Slovakian beet vendor[27], or the Italian salami seller. These peripatetic sellers were usually only found on the edge of regular market areas, as their superior quality and low price of their products was more attractive to the range of local vendors. Blousy jackets and particularly the half-boots mark the Croatian, even the engraver J.C. Brand describes a vendor so dressed as a “Croatian with canvas”.[28] The “Slivowitzverkäufer” (Slivovitz vendor) documented in the Karl Mayer collection[29], a figure of a flask-carrying Croatian, is painted more finely than the figure in the Marton Collection, where the realistic black colour helps us date the figure more exactly.

Whether the Viennese figures of street musicians and actors belong to the Vienna street vendors (Kaufrufe) is a matter of definition. Although conceived as companion figures the street musicians pursued their profession on the street but did not necessarily cry out to sell their “wares”. The bagpipe player and hurdy-gurdy player are dressed in fur jackets. Sladek[30] was able to show not only that these are distinctly jackets of Calabria, but saw also an italian construction in the movement of the dancing marionettes. The Marton Museum’s figure indicate its early date by their delicate pastel colours, the graceful posture and court hairdress and also indicates that again it is a masquerading aristocrat rather than a simple musician. The hurdy-gurdy player exhibits a hoop skirt, a trend of the time, underlining the aristocratic origin.

Picture 4: Apple Seller, Vienna porcelain factory about 1760, H 15,4 cm, Privat collection, Vienna

Picture 5: Detail, Apple Seller from Carl Schütz, „Ansicht des Kohlmarkts“, Vienna 1786

A gender specific division does not necessarily exist within the various levels of vendor groups. Rather, it is the sale of certain products that were reserved for women. Thus we see woman as cooks, wood carriers, tinkers and apple sellers at the market. But the makers of the models often preferred to create figures in pairs, as with the “Pastetenkochin” (pie maker) and “Bratlkoch” (roast cooker). In the Meissen series “Cris de Paris”, there is a model by Peter Reinicke, a Koch mit Bratenspiess (chef cooking on the spit), dated 1753/54 and based on the drawing by Christophe Huet[31], followed the same year by the figure “Koch am Herd” (cook at the stove). Here the modelmaker didn’t forsake the oven details, such as a drawer and stove, while the Vienna figure has just a chicken in his roasting pan. The careful white of the cook’s clothes and aprons is only varied subsequently by a different bonnet.[32] The composition of the figures vary after all according to the time of their creation. In 1760 the plinths are more avant-garde, no longer plump and round, but with a logical linear shape. The figures are supported unobtrusively, as here with the oven. The posture follows a swing of the hips. This, along with the expressively raised arm and head, show a noticeable aplomb. Factory archival texts from 1762 – 1766 reveal, that after the death of Franz I. Stephan of Lorraine in 1765, the figures declined in sales and the Bossierer (modeler) subsequently wasn’t paid as well as before.[33]

Evoking the Rococo as perhaps no other, the “Putzmacherin” (Finerymaker, who made the complex gowns and trims, bonnets, etc.) is not so much a street vendor as the female equivalent of the Wigmaker (Perückenmacher) and both are obviously craftsmen. Kaut considers this profession, much like that of gardener or tailor, to not really be in the Streetvendor (Kaufruf) category, although they do appear in the “Kleiner Kaufruf” of 1777 by Jakob Adam.[34] Again, the courtly posture of the figure, the exquisite table where the wig rests, are a strong contrast to the textured apron, handkerchief and headwear. In a Viennese private collection we find an almost identically painted figure of Finerymaker, which was probably assembled by the same modeler Anton Payer[35], how the figure in the Marton collection. In the extant “conto” (bill) from 1768[36] the Vienna Factory lists “18 simple figures” for the famous Dinner Service for the Abbey in Zwettl (Zwettler Tafelservice). Among these we find “14 figures from the guilds and trades”[37] including the wigmaker, finerymaker woman and the roast cook.

It appears that even the figures made after the appearance of Brand’s engravings of “Kaufrufe” in 1775 are not based on that work but rather on contemporary vendors. One can distinguish more than twenty types of figures that do not derive from a Brand engraving. The figures after 1780 are less carefully but vigorously painted. Many correspond to the vendors in Brand’s examples, yet are not copies. In addition new types were added that did not strictly fit into the concept of “Streetvendor”, such as a gardener, cook and fisherman. How wonderful it would be if one could assemble all 65 of the figures of the Street Vendor (Kaufruf), as categorized by Braun in 1918 to a Panopticum of eighteenth century dining culture and find out where the models came from.

Text in German: Annette Ahrens

English Translation: Edith Steffny

[1] For definition of “Kaufruf” see Kaut, Hubert, Kaufrufe aus Wien, Volkstypen und Strassenszenen in der Wiener Graphik von 1775 – 1914, Vienna 1970, p. 6;

[2] Gregor J.M. Weber, Zwischen Kunst und Natur, Anmerkungen zur Staffage auf Gemälden Bernardo Bellottos in: Seipel, Wilfried (Ed.), Bernardo Bellotto genannt Canaletto, Europäische Veduten, Vienna 2005;

[3] Salomon Kleiner (1700-1761), his works published in Augsburg 1724, 1725, 1733 und 1737;

[4] Lorenz Hellmut, Weigl, Huberta (Ed.), Das Barocke Wien, Die Kupferstiche von Joseph Emanuel Fischer von Erlach und Johann Adam Delsenbach (1719), Wien 2007;

[5] Folnesics, Josef, Braun Edmund Wilhelm, Geschichte der K. k. Wiener Porzellanmanufaktur, Vienna 1907; Braun was director of the museum in Troppau, Silesia (today Opava, Czech Republic);

[6] Braun, Edmund Wilhelm, Ausruferfiguren aus Altwiener Porzellan, in Altwiener Kalender 1918, Vienna 1918, p. 105;

[7] see Braun 1918, p.100;

[8] Eberle, Martin, Cris de Paris, Meissner Porzellanfiguren des 18. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig 2001 after Brandler, Gotthard (Ed.), Eckensteher, Blumenmädchen, Stiefelputzer. Berliner Ausrufer und Volkstypen, Leipzig 1988;

[9] Drawings by Christoph Huet (1692-1765) are in the Archive in Meissen. Some were published by Eberle in 2001;

[10] Sturm-Bednarczyk, Elisabeth (Ed.), Sladek, Elisabeth; Zeremonien, Feste, Kostüme, Die Wiener Porzellanfigur in der Regierungszeit Maria Theresias, Vienna 2007, p. 120 the first series was published in 1775 and not 1755;

[11] practically the first newspaper in German language, founded in Vienna 1703, still existing today as “Wiener Zeitung;

[12] April 22, 1775 “Wiennerisches Diarium” “ …Man glaubt diese charakteristische Nationalabbildungen werden, …, so betitelte Cris für Einheimische und Ausländer nicht uninteressant sein und in Ansehnung des Ausdrucks und der Wahrheit sowie von Seiten des Kupferstichs und der Behandlung Beyfall finden…“ (One would believe these characteristic national sketches ….,so called “Cris” will become of interest for natives and foreigners alike and find acclaim in the anticipation of the expressiveness and truthfulness as well as from the copper engraving as the treatment of the (subject)…);

[13] Beall, Karen F., Kaufrufe und Strassenhändler. Cries and Itinerant Traders, Hamburg 1975, p. 439;

[14] Falke, Otto von, Folnesics, Josef: “Wiener Porzellansammlung Karl Mayer”, Auction Catalogue Glückselig, Vienna 1928. Illus. 120, Nr. 414;

[15] illustrated in Sturm/Sladek 2007 p. 24f, pic. 23, 24, 25;

[16] see Falke/Folnesics 1928, illus. 91, Nr. 300;

[17] see Falke/Folnesics 1928, illus. 91, Nr. 298;

[18] Hofkammerarchiv, NÖ Hoffinanz, Bancale 620, fol.880-906;

[19] Schemper-Sparholz Ingeborg, Lorenzo Mattielli, Boreas raubt Oreithyia. Gruppe aus dem Schwarzenberggarten in: Hellmut Lorenz(Hg.), Geschichte der bildenden Kunst in Österreich. Barock. München 1999, p. 504f;

[20] Umprum Praha, Inv.Nr. 79.304;

[21] Compare a example of this rare vendor figure in the Hetjens-Museum, Düsseldorf;

[22] Diary of Johann Joseph Prince Khevenhüller-Metsch, lord chamberlain to the Empress, 1742-1776. Documentation by Elisabeth Grossegger, “Theater, Feste und Feiern zur Zeit Maria Theresia 1742-1776, Vienna, 1987, p. 268;

[23] Day, Ivan. “Royal Sugar Sculpture”, Bowes Museum 2002;

[24] See Lorenz/Weigl 2007, table 14, “Prospect des hohen Marckts zu Wien”;

[25] In the MAK Vienna /Museum für Gegenwartskunst there is a model of the Croatian Flaskseller with a squarish base, which dates presumably earlier. Also a figure with almost identical painting is in Sturm/Sladek 2007, p.116, illus.171;

[26] Krammer, Otto, Wiener Volkstypen, Vienna 1983; p. 151;

[27] Collection Selma von Strasser in Budapest, as pictured in Braun 1918, p.112f;

[28] Sturm/Sladek 2007, p.123, identified as a Hungarian costume;

[29] Falke, Otto von, Folnesics, Josef, “Wiener Porzellansammlung Karl Mayer”, Auction Catalogue Glückselig Vienna 1928, Illus. 117, Nr. 392; The 1914 published catalogue of the famous collection of Karl Mayer (1855-1942) illustrates over 500 Vienna porcelain pieces, which 1928 were sold by auction. Some pieces bought the Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Vienna;

[30] Sturm/Sladek 2007, p.196, illus.301; Street musician with marionettes (dated ca. 1760) Painter Nr. 20, Former Q, height: 20,2cm, (Variation with different painting and without gold border on the base belongs to the art dealer)

[31] Eberle 2001, p.80, 86, a drawing called “…einen Braten-Meister welcher einen “Welschen Hahn” ansteckt…”;

[32] Compare Collection Karl Mayer 1928, illus.114 (a variation of cook’s hat and roast on the oven) and see Sturm /Sladek 2007, p.112, illus. 158 (more vigorous painting of the pair);

[33] Folnesics/Braun 1907, p.180;

[34] Draughtsman and engraver Jacob Adam (1748-1811) published a “People’s edition” of “Abbildungen des gemeinen Volks zu Wien” with 100 numbered copper engravings which, in contrast to Brand showed the working populace truer to the original and called them by their Vienna Dialect names.

[35] Neuwirth Waltraud, “Wiener Porzellan – Original, Kopie, Verfälschung, Fälschung”, Vienna 1979, p.569. Modeler Anton Payer 1762-1787 mentioned in the payment lists of the manufactory;

[36] Neuwirth, Waltraud, “Zur Geschichte des “Zwettler Tafelaufsatzes” from “alte und moderne kunst” 170/1980, p.2-7;

[37] “Wien 1904”, an exhibit of Old Vienna Porcelain, K.k. Österr. Museum für Kunst und Industrie, Vienna 1904, p.85. 1904 still in the possession of the Abbey, the “Zwettler Tafelaufsatz” first came to the Museum for Applied Arts in Vienna in 1926. Inv. Nr. Ke 6823, where it is display until today.;

Literaturtip:

Veljko Marton (Hg.), European Porcelain from the Marton Museum Collection, Embassy of Croatia, London 2008 (in englischer Sprache) ISBN 978-953-99897-4-1